Achieving 3-Second Latency in Streaming: A Deep Dive into LL-HLS and LL-DASH Optimization with CDN

- December 15, 2025

- 9 min read

HLS/DASH streaming via CDN with ~3 seconds latency glass-to-glass

LL-HLS and LL-DASH are well-documented standards, but delivering them reliably at scale is far from trivial. The challenge is not in understanding the protocols—it is in engineering, operating, and debugging a low-latency pipeline under real production traffic. Achieving stable 2–3 second latency requires precise coordination across encoding, packaging, transport, and CDN edge behavior.

Over the past years, Gcore has developed deep practical expertise in low-latency transcoding and global delivery, refining our architecture through extensive field experience. This enables us to consistently reach ~2.0 seconds on LL-DASH and ~3.0 seconds on LL-HLS across a global network.

This article outlines the core technical insights and production-proven optimizations that make our low-latency platform work, focusing on the real constraints and solutions encountered at scale, not just the theory behind the protocols.

As a result, we were able to set up all stages: transcoding, packaging, and delivery.

Challenge of low-latency

The low-latency standards introduce mechanisms that fundamentally change media delivery behavior.

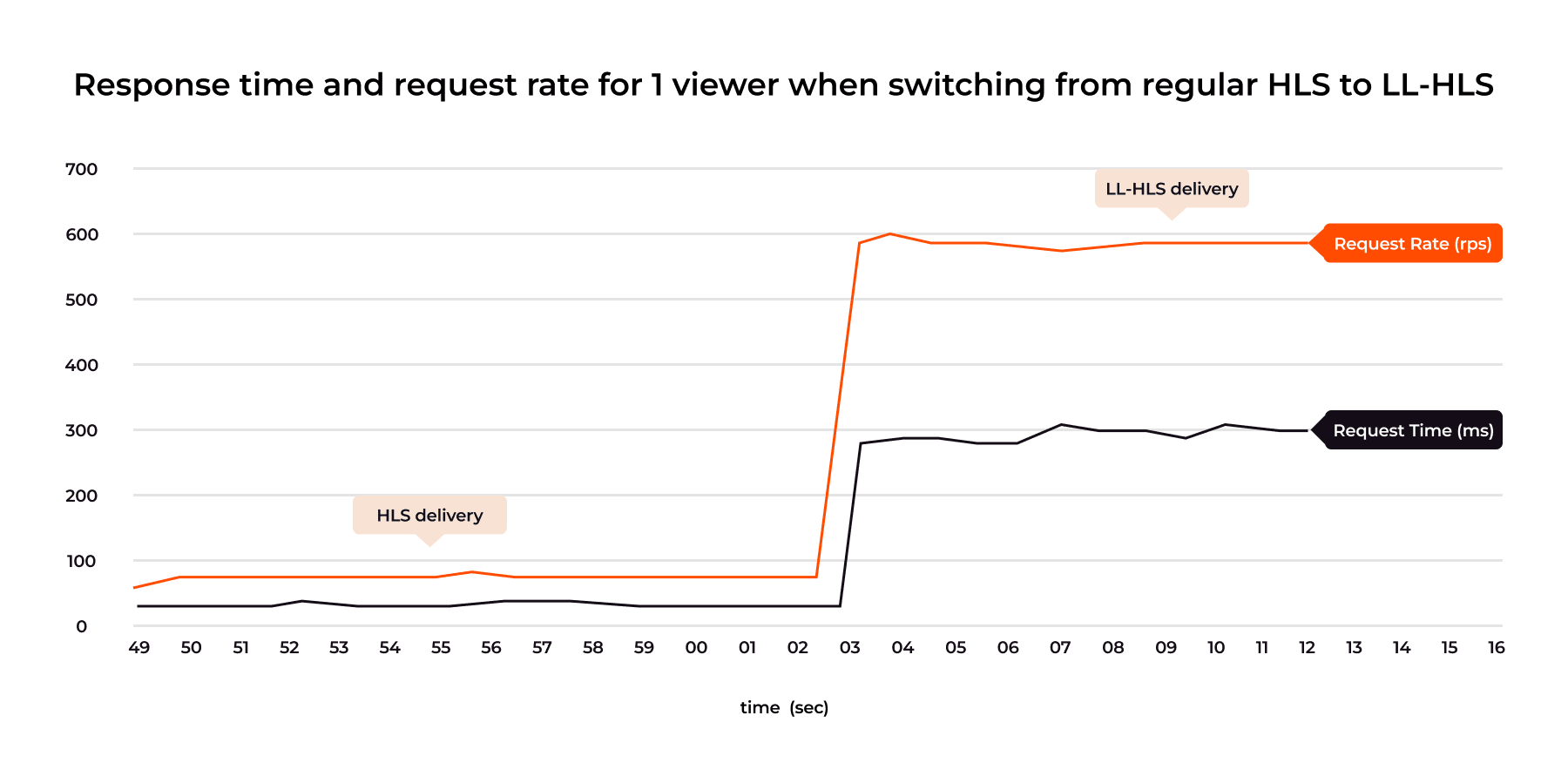

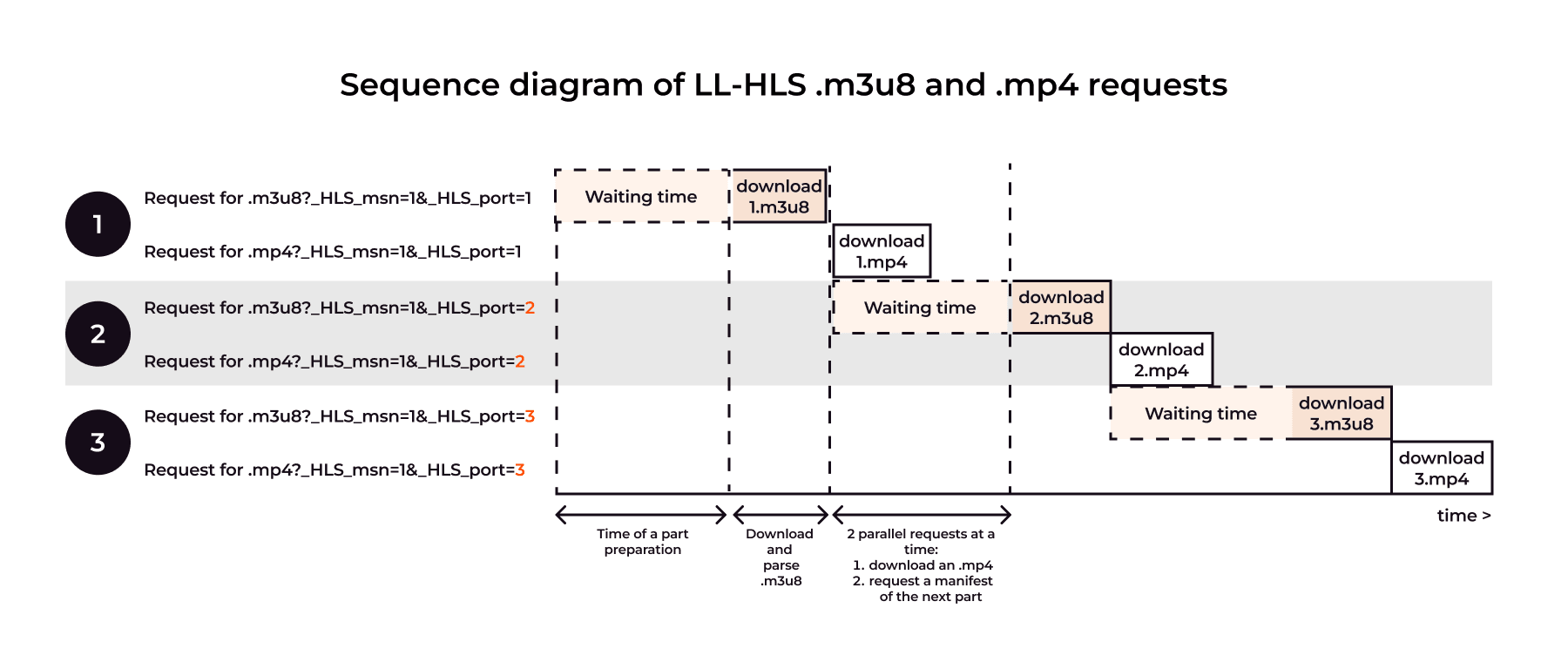

For example, request rates increase sharply, and certain objects must be held on the server until new content is ready, for LL-HLS this is the “Blocking Playlist Reload” feature. These mechanics make traditional CDN monitoring misleading. Metrics like “response_time”, once a primary indicator of performance, no longer reflect actual latency or delivery quality in a low-latency workflow.

This diagram highlights a counterintuitive behavior: as request volume grows, response times rise, even for very small segments. This surprises teams new to low-latency workflows, but it reflects real-world queueing and synchronization overhead that traditional architectures were never designed to handle.

LL-DASH introduces additional complexity through long segment durations, 10-second MP4 fragments make low-latency delivery impossible under standard “download-first-deliver-later” CDN behavior. To provide consistent latency across formats, we needed to unify transcoding, packaging, and CDN delivery into a single synchronized pipeline.

With this architectural shift, the traditional and low-latency delivery paths diverged as follows:

Unified low-latency transcoder

The first thing we had to figure out was how to combine the processing of the two protocols into a single workflow.

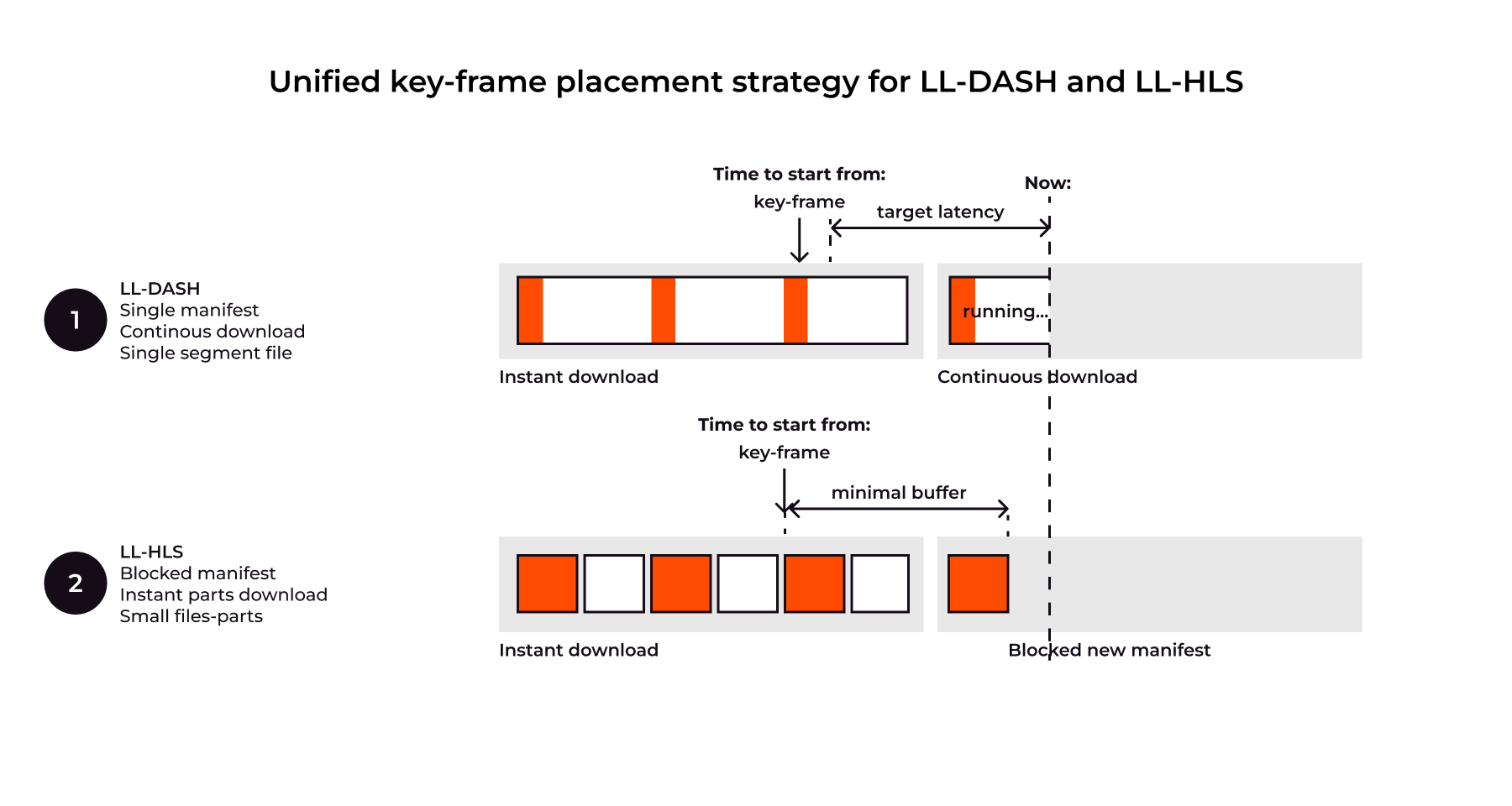

LL-DASH is flexible but complex. Key principles are: single manifest, time-based chunk requests, and continuous download of in-progress chunks. Crucially, playback starts only at a keyframe, making keyframe frequency, not segment duration, the primary determinant of achievable low latency. While balancing latency and stability, LL-DASH is sensitive to network variations and update delays.

LL-HLS requires different delivery mechanisms: Manifest Blocking, Short Manifests, and tiny, rapidly generated parts. The critical feature, Blocking Playlist Reload (CAN-BLOCK-RELOAD=YES), holds the manifest request until the next part is ready, meaning the manifest response time reflects content preparation, not CDN speed. Latency is affected by the local buffer, the number of generated parts, and again, the keyframe frequency. Like LL-DASH, keyframe frequency is a key latency parameter, regardless of full segment length. The specification also allows for byte-range requests, which affect delivery but not final delay.

To ensure genuine low latency, it is essential to move beyond treating LL-DASH and LL-HLS as separate, independently timed pipelines. The optimal strategy is to unify these formats during the transcoding and packaging phases, guaranteeing that they share identical keyframe cadences, segment part boundaries, and availability timelines.

With this foundation in place, we can now combine to create a single scheme for placing key frames and distributing streams:

Full-fledged low-latency ABR

We transcode into a full-fledged ABR with multiple ladders: 360p, 468p, 720p, and 1080p. The entire ladder comes out simultaneously and synchronized for all protocols: LL-HLS, LL-DASH, and legacy HLS. At the output segments are generated in 2 containers at once: CMAF (with fragmented mp4, fmp4) and MPEG TS (.ts).

We also pay great attention to uninterrupted transcoding. As you know, mobile Internet of users-hosts means an unstable connection to the server, so transcoding must be able to handle situations related to changing FPS and changing the image size. This is especially important for WebRTC.

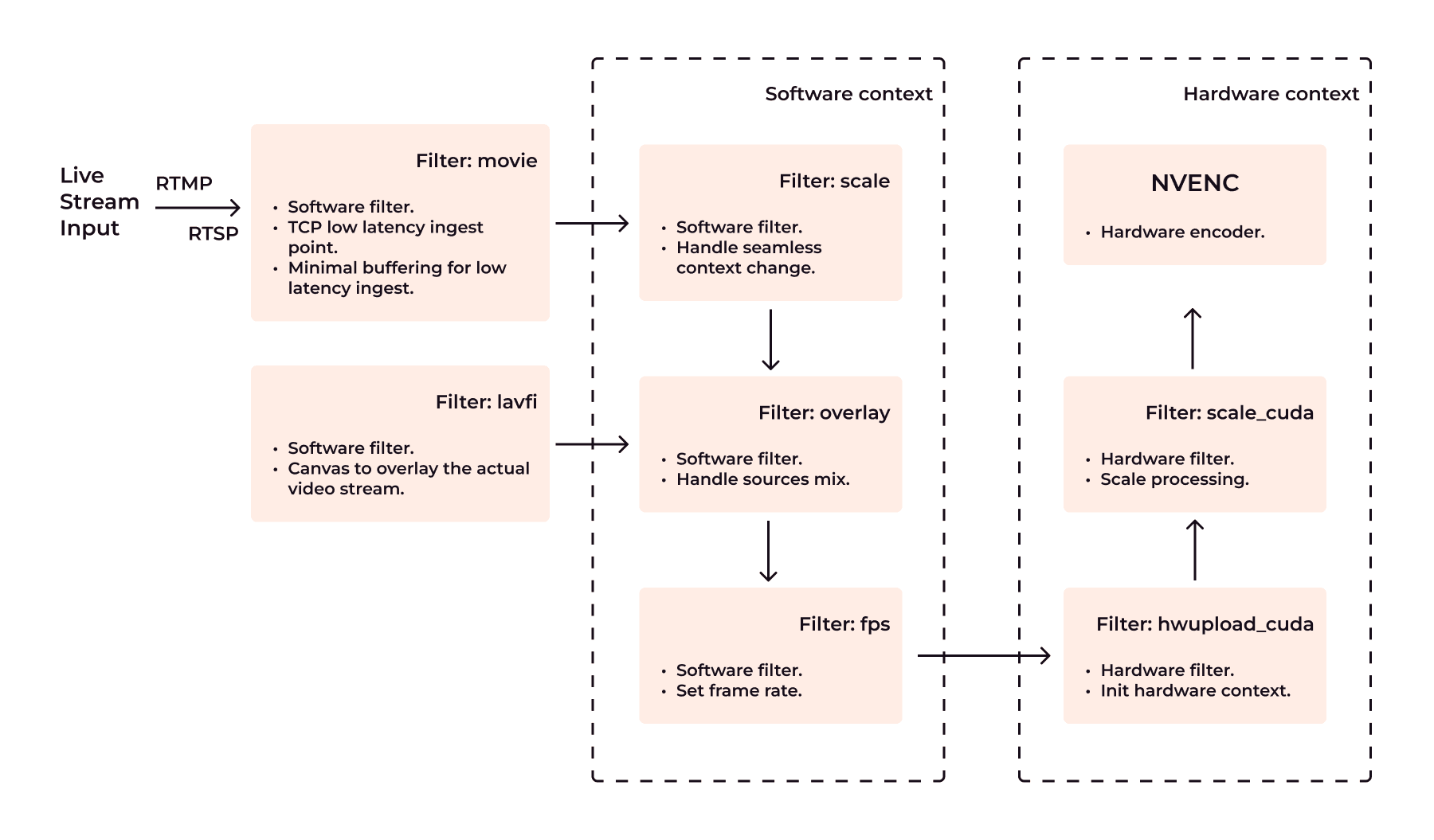

Following the unification principles, we use both GPU (Nvidia/Intel) and software-based workflows to target max processing pipeline flexibility. GPU workers could offload decoder/encoder parts to lower processing latency while keeping original color formats (like HDR+) for best quality. Software workers and filter chains help us to handle context change cases, where video frame resolution or FPS can change instantly, so we need to keep workflow up in such cases.

Low latency live streaming workflow powered by GPU and context change handling:

Below are some of the optimizations we use in our system. We've included examples based on the open-source FFMPEG command for clarity.

Scaling and Overlay:

- This part allows us to handle dynamic resolution change without transcoding restarts.

[movie_v]scale=w=-2:h=1080[movie_v_scaled]; [0:v][movie_v_scaled]overlay=x=(W-w)/2:y=0:eof_action=endall[movie_v_overlayed]- Scales the stream vertically to 1080p (-2 preserves aspect ratio).

- Overlays it on the center of the black background.

Frame Rate and GPU Upload:

- Prepare frame upload to selected GPU (Nvidia in this example)

[movie_v_overlayed]fps=30:start_time=0:round=near,hwupload_ cuda=device=1[movie_o]- Ensures 30 fps.

- Uploads the video to CUDA GPU.

Unified low-latency just in time packager

This created a new problem because the packager had to handle both low-latency and regular streams. Our new universal packager now can create 3 types of content at once from the same transcoding source:

- LL-DASH CMAF

- LL-HLS CMAF

- HLS MPEGTS

At the same time, we retained the ability for low latency streams to have an audio track as a separate track. That is, there are many audio tracks with different voiceovers in different languages here as well.

A large number of studies conducted by us and other providers show the ratio of key-frame rate to transmitted bitrate. More key-frames – more bitrate and less quality. Look at THEO https://www.theoplayer.com/blog/how-to-optimize-ll-hls-for-low-latency-streaming, OvenMediaEngine https://medium.com/@OvenMediaEngine/low-latency-hls-the-era-of-flexible-low-latency-streaming-ec675aa61378 as an example.

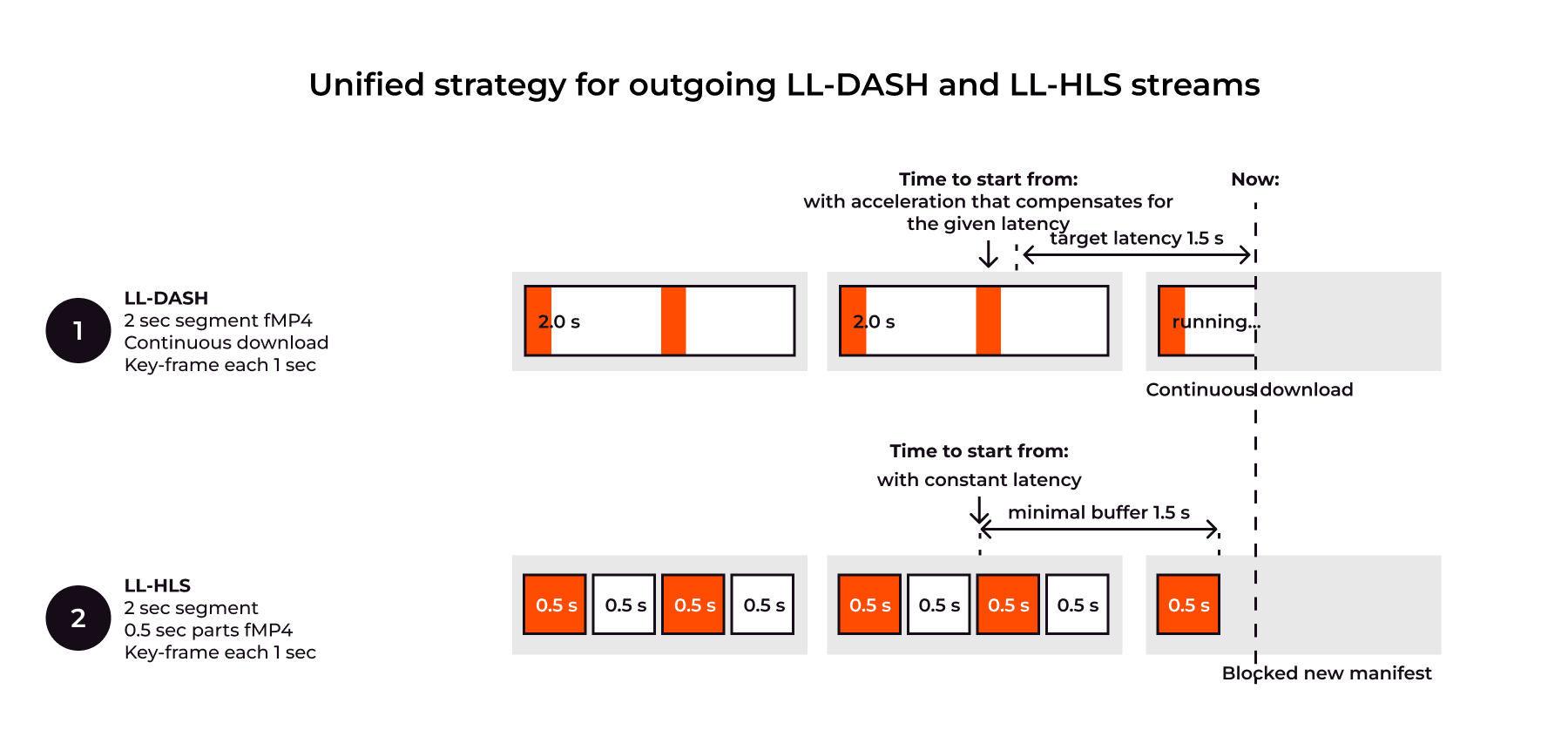

Our experiments resulted in the following parameters that are rendered in the outgoing manifests and parts:

- Segment size = 2 sec. Allows to make small files for LL-DASH and HLS MPEGTS.

- Part size = 0.5 sec. Allows to cut parts for LL-HLS into small segments while maintaining low latency.

- GOP = 1sec. This allows the player to start playback as quickly as possible with a 0-1000ms wait from pressing play button.

- Minimal buffer = 1.5sec. This allows players to keep latency low and keep a buffer during last mile download issues.

Low-latency delivery via CDN

Here, development of CDN delivery also proceeded in two streams, and then merged into a single solution.

First, let's look at the delivery features of both protocols:

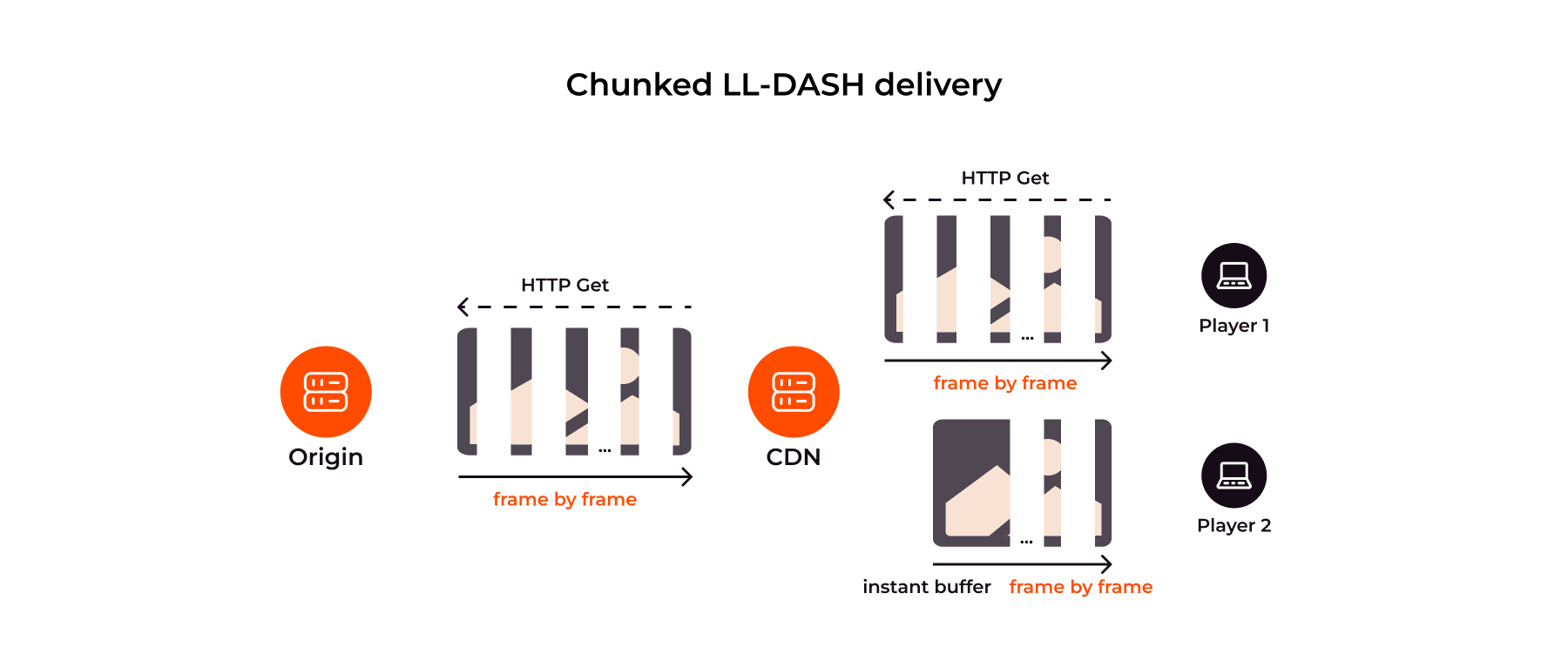

LL-DASH: Chunked transfer. CDN must be able to distribute files partially downloaded from the origin. Thus, configs of regular servers such as Nginx:proxy_cache_lock and Nginx:proxy_buffering are not suitable. A new mechanism was needed to cache part of the received file.

Explanation of chunked cache and delivery LL-DASH over CDN:

LL-HLS: Blocked origin requests. CDN must hold manifest requests until the next part is ready, making traditional “response_time” metrics irrelevant. MISS and EXPIRED states must trigger only a single origin fetch, requiring custom logic beyond what proxy_cache_lock can provide.

CDN must be prepared for an increased number of requests for tiny files: low latency manifests for each new part, and parts-files. Yes, the file size is very small, but the number of requests is terribly large: 1 single segment contains N manifests, and N parts-files. Logs alone become approximately 2*N times larger, monitoring and analysis tools had to be optimized too.

By combining both approaches in one architectural solution, we developed a new module from scratch, which we call “chunked-proxy”. The new module downloads bytes from the origin and immediately begins distributing them to end-users. Each new connected user instantly receives the full volume of the already accumulated cache and then continues to receive other bytes through continuous download simultaneously with all other users.

I use the term "Chunked transfer" here with caution. If connection is HTTP/1.1, it would be a chunked transfer response, for HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 it would be a framing.

Chunked-proxy is created as a full-fledged caching module according to CDN standards, its features include caching GET and HEAD requests in RAM.

It's high time to remember the Byte-Range requests from LL-HLS specification here. Because thanks to this feature, it’s possible to reduce the number of requests several times. There will be 1 request for one segment, instead of N requests for discrete file parts. According to the HLS specification (https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/draft-pantos-hls-rfc8216bis-16#section-6.2.6) "When processing … a byte range of a URI that includes one or more Partial Segments that are not yet completely to be sent … the server MUST refrain from transmitting any bytes belonging to a Partial Segment until all bytes of that Partial Segment can be transmitted at the full speed of the link to the client." It means that transmission to and from CDN should be organized through the "Chunked proxy" as for LL-DASH, but with an explicit logical division into parts. This functionality will soon be supported by us.

Some more technical points we encountered

Low latency ingest optimisations of RTMP, SRT

The main task is to set the parameters for creating an origin stream with parameters that would subsequently allow spend less time on receiving and transcoding.

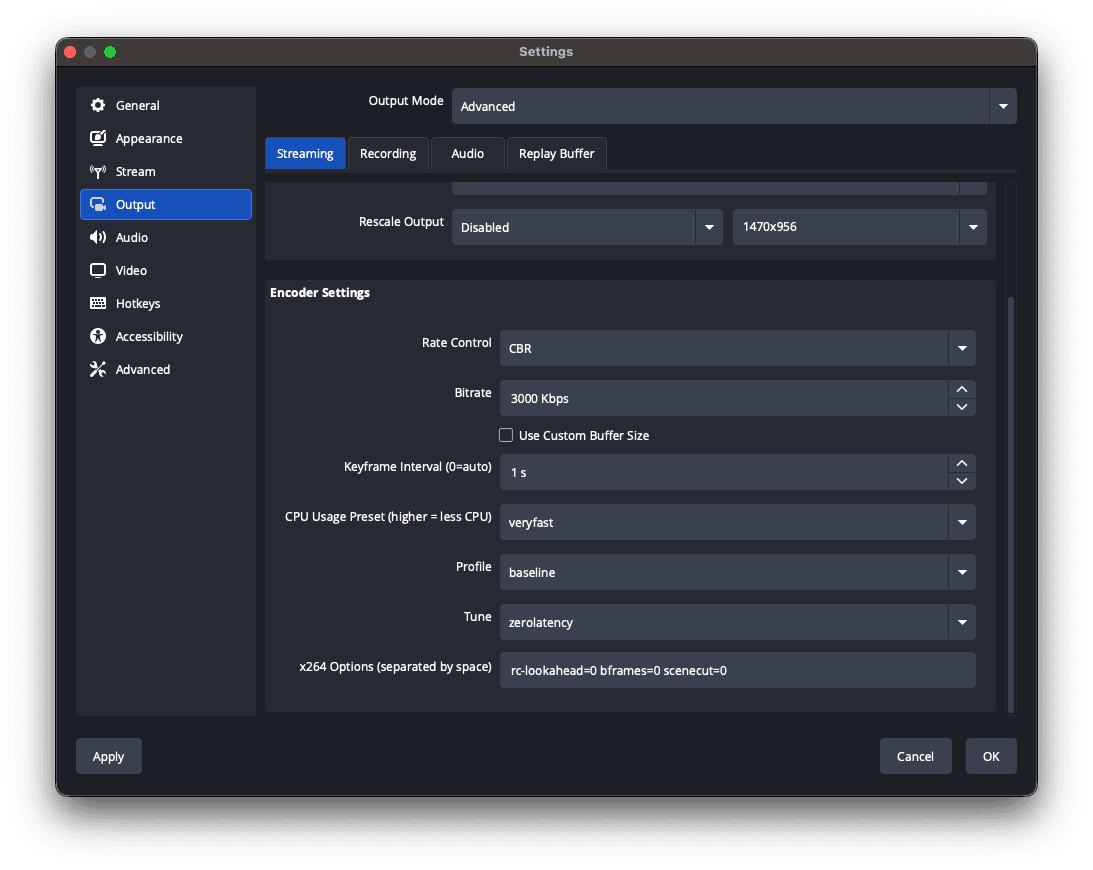

Numerous tests have shown that the flow needs to be simple and predictable, so pay attention to the parameters on example of OBS:

Video:

- Rate Control = CBR (constant bitrate). CBR is used to send a consistent bitrate throughout the stream.

- Bitrate = 2.0-4.5Mbps. Select a bitrate no more than you expect to see in the output’s maximum resolution.

- FPS = 30. So 30 frames per second provides smooth motion for most streaming.

- CPU Usage Preset = VeryFast. Use the preset that minimizes CPU usage and produces results as quickly as possible.

- Codec = H.264.

- Tune = “zerolatency”. Optimizes encoder for low-latency streaming by prioritizing speed over compression.

- Options = “rc-lookahead=0 bframes=0 scenecut=0”. Disable lookahead queue, B-Frames and scene-cut detection, enable more predictable keyframe placement.

Audio:

- AAC, 128+ kbps

Or you can prepare ffmpeg for low-latency streaming. Example of an ffmpeg command that removes b-frames and sets fast encoding (you can add CBR and other options by yourself):

ffmpeg -re -stream_loop -1 -i "Blender Studio/Coffee Run.mp4" -c:a aac -ar 44100 -c:v libx264 -profile:v baseline -tune zerolatency -preset veryfast -x264opts "rc-lookahead=0 bframes=0:scenecut=0" -vf

"drawtext=fontsize=(h/15):fontcolor=yellow:box=1:boxcolor=black:text='%{gmtime\:%T}.%{gmtime\:%3N}UTC, %{frame_num}, %{pts\:hms} %{pts} %{pict_type},

%{eif\:h\:d}px':x=(w-tw)/2:y=h-(4*lh)" -hide_banner -f flv

"rtmp://vp-push-ed1.gvideo.co/in/12345?aa...aa"Visual Filter here just adds debug info such as local time and PTS into the video frame, so you have ability to compare delivery time glass-to-glass.

Low-latency ingest via WebRTC WHIP

To receive the stream via WebRTC from a generic browser we use WHIP. WebRTC is transmitted to the transcoder in the pass-through format. Then the same operating scheme is applied as with the usual RTMP/SRT.

The original WebRTC stream must have the following encoding parameters:

- Video codec: H.264 with fast encoding and no B-frames (look details in the section above). Keyframe is each 1s.

- Audio codec: Opus.

The biggest challenge was to ensure smooth delivery from a host in a regular browser to the video receiving server over the public Internet.

Network issues:

- We have implemented TCP Relay data transmission,

- and for the most complex cases we have included additional TURN-servers to ensure better delivery.

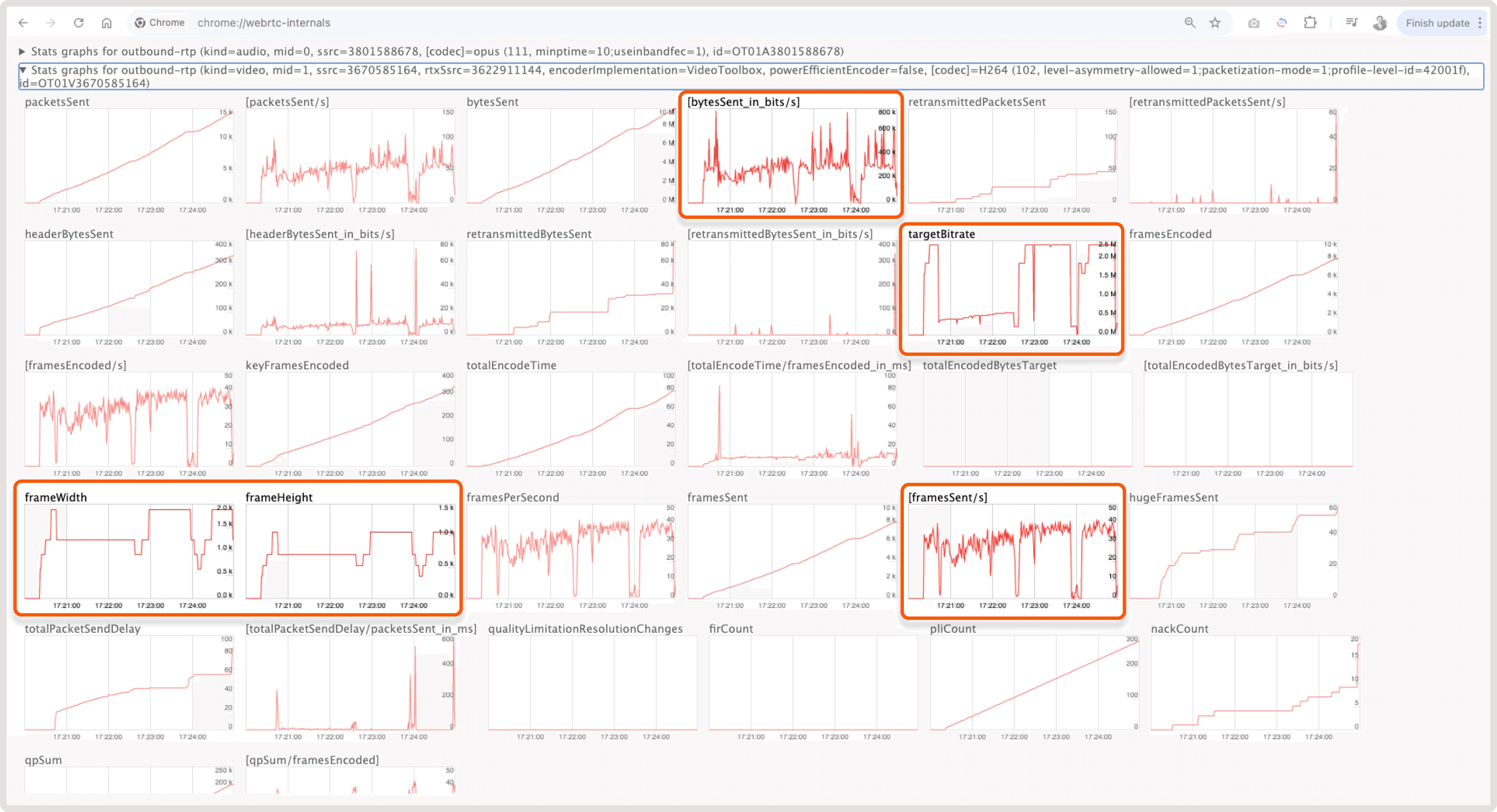

In WebRTC, the browser locally makes a decision on the parameters for sending a stream and frames based on the conditions of the last mile Internet quality, CPU load on the device, etc. This introduces variability into the stream ingest and transcoding scheme. For example, look below at how unevenly frames are sent from the browser, the settings above allowed us to stabilize the delivery and transcode.

Problems with variable frame sending in WebRTC:

- Variable frameWidth, frameHeight – The image size may change over time depending on the sending conditions on the client. Ingester and transcoder are prepared to work with variable image size.

- Variable framesSent/s – The number of frames can also change over time. Moreover, the values can be from 0 to maximum. Ingester and transcoder are prepared to work with variable FPS.

- Variable targetBitrate – In addition to the size, the browser also determines the compression level by setting the target bitrate value. Be prepared for unexpectedly poor quality on transcode.

- Variable bytesSent_in_bits/s – All these changes will be visible on the graph of the sum of bytes sent with noticeable dips. At such moments, the transfer stops completely. We had to set up a long transcoding under the condition of no data from the origin.

More details you can find in our article of how to manage WebRTC WHIP here https://gcore.com/docs/streaming/live-streaming/protocols/webrtc

iOS Safari with LL-HLS playback

Without going far from the playback of LL-HLS, a few words about Safari. It is constantly being improved, but this is reflected in the behavior and reproduction of LL-HLS natively. Different versions behave so differently that the implementation is obtained with a delay of 2 to 7 seconds with large unpredictable hops. Or the quality does not rise above 480p.

Also pay attention to downloading speed (not response_time) of the first master manifest, and the first low-latency manifests. Based on downloading speed of these files, the possibility of turning on LL is determined. Don’t forget to control parts and information about them in manifests. In case of any discrepancies in video or audio parts, there will be a switch to normal latency with a delay of up to 20-30 seconds.

You will need to use “Media Stream Validator” from Apple’s tools to verify manifest (https://developer.apple.com/documentation/http-live-streaming/using-apple-s-http-live-streaming-hls-tools). But be warned that even if this tool shows full compatibility, the stream still may not play in Safari :)

LL-HLS ~1.5 seconds latency

Reducing chunk/part duration to 0.2 seconds significantly decreased total latency from 3 seconds to ~1.5 seconds. This is a key benefit of LL-HLS, as it allows the transmission of smaller units of segments.

But this reduction is a balancing act between latency and quality. Our tests have shown that lower values often result in buffering for the end viewer.

iOS Safari with LL-HLS and LL-DASH playback

One more thing to note about LL-DASH is that it's starting to be supported on MacOS/iPadOS and iOS too. MSE (Media Source Extensions) is supported by older MacOS versions, and iPadOS 13+. Finally thanks to Apple for starting to support MMS (Managed Media Source) in iOS version 17.1 (https://webkit.org/blog/14735/webkit-features-in-safari-17-1/). The developers at dash.js have supported this feature as well.

Thus, for iOS you can use the following:

- iOS 17.1+ with MMS support – LL-DASH with 2,0 sec low latency.

- iOS 14.0+ with LL-HLS support – LL-HLS with 3,0 sec low latency.

- iOS 10.0+ with HLS CMAF support – LL-HLS but with ±9 sec reduced latency.

- other iOS devices – traditional HLS MPEGTS with ±9 sec reduced latency.

Conclusion

The technical guidance above shows how to use low-latency protocols effectively, but achieving consistent performance in production requires coordinated changes across transcoding, packaging, monitoring, and CDN delivery. Gcore has already solved these challenges at scale, delivering ~2.0-second LL-DASH and ~3.0-second LL-HLS globally.

With Gcore’s proven low-latency architecture, you gain a production-ready, globally scalable CDN solution that can deliver glass-to-glass latency of 2 to 3 seconds for both CDN-only and full transcoding-plus-CDN delivery customers. Don't hesitate to contact us to leverage our expertise.

Related articles

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest industry trends, exclusive insights, and Gcore updates delivered straight to your inbox.