Gcore Blog

Discover the latest industry trends, get ahead with cutting‑edge insights, and be in the know about the newest Gcore innovations.

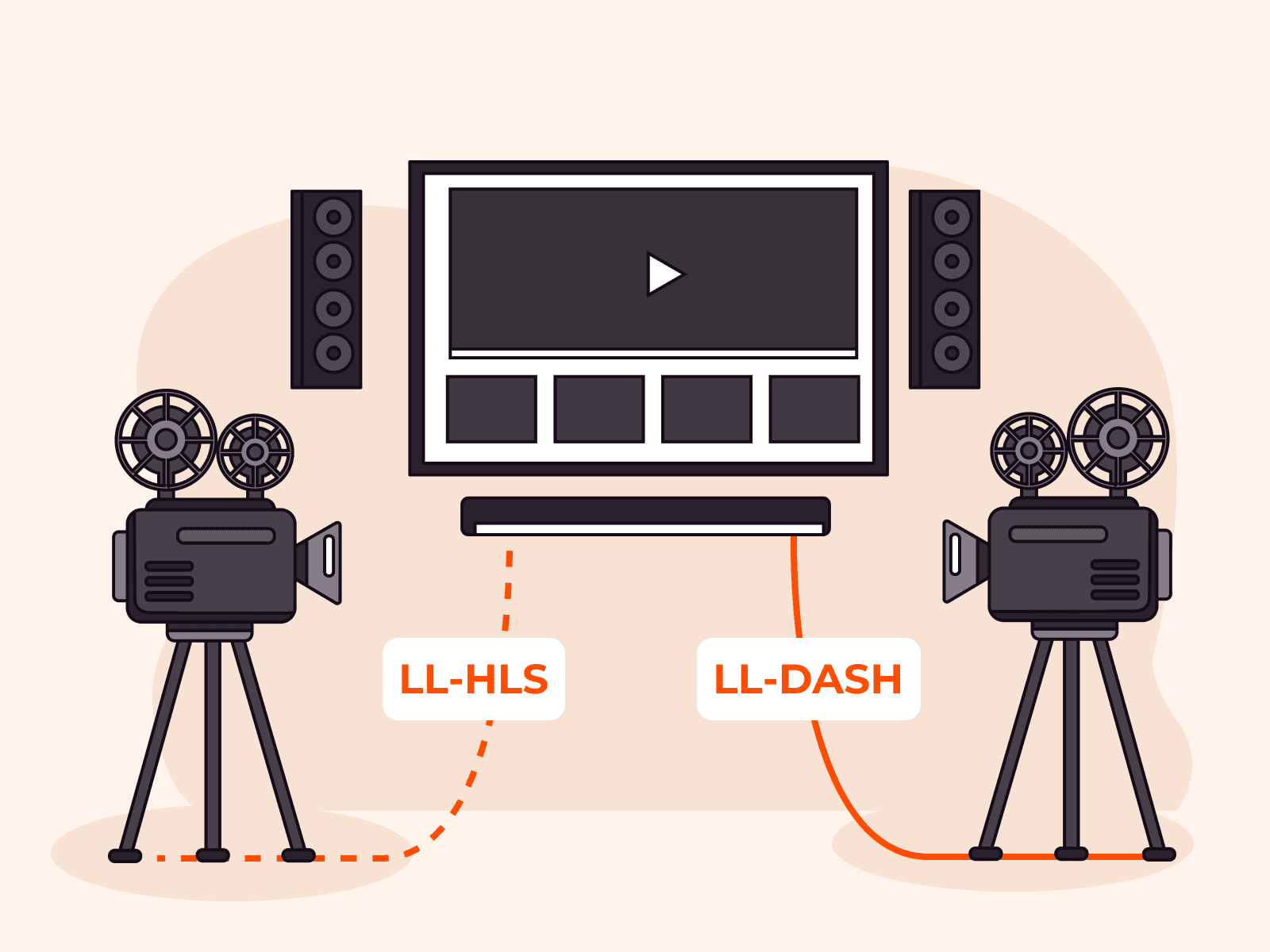

HLS/DASH streaming via CDN with ~3 seconds latency glass-to-glassLL-HLS and LL-DASH are well-documented standards, but delivering them reliably at scale is far from trivial. The challenge is not in understanding the protocols—it is in engin

We’ve expanded our AI inference Application Catalog with three new state-of-the-art models, covering massively multilingual translation, efficient agentic workflows, and high-end reasoning. All models are live today via Everywhere Inference

We’ve expanded our Application Catalog with a new set of high-performance models across embeddings, text-to-speech, multimodal LLMs, and safety. All models are live today via Everywhere Inference and Everywhere AI, and are ready to deploy i

For enterprises, telcos, and CSPs, AI adoption sounds promising…until you start measuring impact. Most projects stall or even fail before ROI starts to appear. ML engineers lose momentum setting up clusters. Infrastructure teams battle to b

At Gcore, delivering exceptional streaming experiences to users across our global network is at the heart of what we do. We're excited to share how we're taking our CDN performance monitoring to new heights through our partnership with AVEQ

Viewers in sports, gaming, and interactive events expect real-time, low-latency streaming experiences. To deliver this, the industry has rallied around two powerful protocols: Low-Latency HLS (LL-HLS) and Low-Latency DASH (LL-DASH).While th

Gcore recently detected and mitigated one of the most powerful distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks of the year, peaking at 6 Tbps and 5.3 billion packets per second (Bpps).This surge, linked to the AISURU botnet, reflects a growing

We’re pleased to announce two new premium features for Gcore CDN: Dedicated IP and Bring Your Own IP (BYOIP). These capabilities give customers more control over their CDN configuration, helping you meet strict security, compliance, and bra

Enterprises and cloud providers face major roadblocks when trying to deploy GPU infrastructure at scale: long time-to-market, operational inefficiencies, and difficulty bringing new capacity to market profitably. Establishing AI environment

Cyberattacks are becoming more frequent, larger in scale, and more sophisticated in execution. For businesses across industries, this means protecting digital resources is more important than ever. Staying ahead of attackers requires not on

Edge AI isn’t just a technical milestone. It’s a strategic lever for businesses aiming to gain a competitive advantage with AI.As AI deployments grow more complex and more global, central cloud infrastructure is hitting real-world limits: c

As streaming demand surges worldwide, providers face mounting pressure to deliver high-quality video without buffering, lag, or quality dips, no matter where the viewer is or what device they're using. That pressure is only growing as audie

Game development is in a pressure cooker. Budgets are ballooning, infrastructure and labor costs are rising, and players expect more complexity and polish with every release. All studios, from the major AAAs to smaller indies, are feeling t

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest industry trends, exclusive insights, and Gcore updates delivered straight to your inbox.