Low latency for LIVE streams

Gcore offers specific latency numbers to customers, providing advanced low-latency streaming options:| Protocol | Format | Latency | Latency Level | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL-DASH | CMAF | 2–4 seconds | Low Latency | Chunked download of partially ready files from origin, quick segments download. |

| LL-HLS | CMAF | 3–5 seconds | Low Latency | Quick segments and parts download, manifest blocking. |

| HLS | MPEG-TS | ~9 seconds | Reduced Latency | Reduced chunk sizes and optimizations for fast manifest and file delivery. |

What is low-latency?

Streaming latency is the timespan between the moment a frame is captured and when that frame is displayed on the viewers’ screens. Latency occurs because each stream is processed several times during broadcasting to be delivered worldwide:- Encoding (or packaging). In this step, the streaming service retrieves your stream in any format, converts it into the format for delivery through CDN, and divides it into small fragments.

- Transferring. In this step, CDN servers pull the processed stream, cache it, and send it to the end-users.

- Receipt by players. In this step, end-user players load the fragments and buffer them.

How does Gcore provide low latency?

The Gcore Video Streaming receives live streams in RTMP or SRT protocols; transcodes to ABR (adaptive bitrate), via CDN in LL-HLS and LL-DASH protocols.| Protocol | Name | Details |

|---|---|---|

| LL-HLS | Low Latency HTTP Live Streaming | Based on constantly changed manifests with extra information about last parts to be downloaded. Requires full speed of downloading when files are ready on origin. Requires manifest blocking on the server. |

| LL-DASH | Low Latency MPEG-DASH | Based on partially completed files that must be continuously downloaded from the origin, it is distributed as new portions of data are received from the file. |

- Faster Delivery: Small chunks can be sent over HTTP networks immediately as they are encoded, without waiting for the full segment to complete.

- Compatibility: A single set of media files works for both HLS and DASH players, reducing storage and encoding costs.

- Low Latency: Enables “Chunked Encoding” where playback can begin while the file is still being downloaded.

Gcore’s Implementation: Unified Pipeline & Chunked-Proxy

To realize this low-latency potential at scale, Gcore employs specific optimizations described below. For full details deep dive into our tech article Achieving 3-Second Latency in Streaming: A Deep Dive into LL-HLS and LL-DASH Optimization with CDN in the blog.1. Transcoding: Unified Pipeline Engine

If you use our Streaming ingest and transcoding service. Our Unified Low-Latency Transcoder and Just-in-Time Packager process LL-DASH and LL-HLS simultaneously. This synchronization ensures that both protocols share identical keyframes, segment boundaries, and availability timelines, eliminating the “drift” often seen in multi-protocol delivery. To achieve this, we enforce strict parameters:- GOP: 1 or 2 second (Ensures rapid seek and playback start).

- Segment Size: 2 seconds.

- Part Size: 0.5 or 1 second (Allows players to download content in tiny increments).

- Minimal Buffer: 1.5 seconds.

2. Low-Latency CDN Delivery: Chunked-Proxy

If you use our CDN delivery service. Standard CDNs typically wait for a file to be completely downloaded from the origin before sending it to the user (“Store and Forward”). Gcore uses a proprietary Chunked-Proxy module that streams data immediately:- Immediate Distribution: The CDN edge begins sending bytes to the user while they are still being received from the origin.

- Protocol Optimization: Uses Chunked Transfer Encoding for HTTP/1.1 and Framing for HTTP/2 & HTTP/3 for partially ready files.

- Smart Caching: Efficiently handles the high volume of requests for tiny parts and Blocking Playlist Reloads.

How to use low latency streaming

Low Latency streaming is enabled by default. It means your live streams are transcoded to HLS, LL-HLS, and LL-DASH protocols automatically. Links for embedding the live stream to your own player contain the /cmaf/ part and look as follows:- LL-HLS, CMAF (low latency):

https://demo.gvideo.io/cmaf/2675_19146/master.m3u8 - LL-DASH, CMAF (low latency):

https://demo.gvideo.io/cmaf/2675_19146/index.mpd - Traditional HLS, MPEG TS (no low latency):

https://demo.gvideo.io/mpegts/2675_19146/master_mpegts.m3u8

Direct link to the player: https://player.gvideo.co/broadcasts/2675_21606

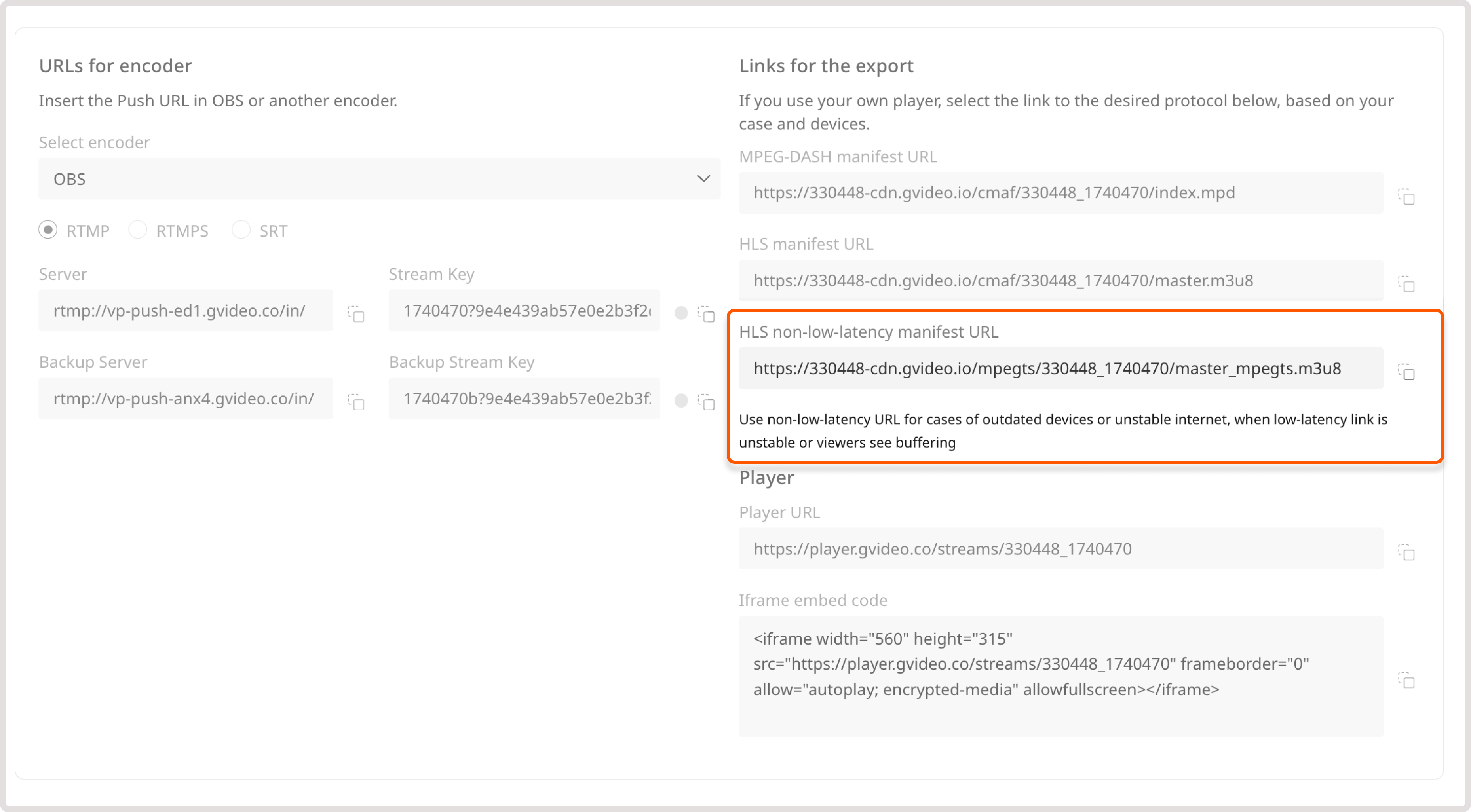

Switch to legacy HLS modes

Some legacy devices or software require MPEG-TS (.ts) segments for streaming. To ensure full backward compatibility with HLS across all devices and infrastructures, we offer MPEG-TS streaming options. We produce low-latency and non-low-latency streams in parallel, so you don’t have to create a stream specifically for cases when the connection is unstable or a device doesn’t support low-latency. Both formats share the same segment sizes, manifest lengths for DVR functionality, and other related capabilities. You can get the non-low-latency in the same Links for export section in the Customer Portal:- On the Video Streaming page, find the needed video.

- In the Links for export section, copy the link in the HLS non-low-latency manifest URL field. This link contains non low-latency HLSv3 and MPEG TS files as chunks.

Tips for low latency ingest

Low‑latency ingest is all about minimising buffering across the capture–encode–transmit pipeline.Each step introduces delay: encoders buffer frames to make better compression decisions, the network adds jitter, and downstream transcoders and segmenters wait for clean GOP boundaries. To achieve sub‑second latency you must tune the encoder and pipeline for real‑time operation:

- Disable B‑frames and scene‑cut detection. Many codecs use B‑frames and variable GOPs for compression efficiency. These require buffering multiple frames and cause unpredictable key‑frame spacing. FFmpeg’s x264 encoder exposes a special tuning preset for live streaming:

-tune zerolatency, which disables B‑frames and reduces internal buffering. - Use a fast preset and 4:2:0 colour format. Real‑time encoding trades compression for speed. A

veryfastorultrafastpreset lowers CPU usage and latency. Constraining the pixel format toyuv420p(I420) avoids 4:4:4 output, which some ingest servers reject when operating in baseline mode. - Fix the GOP length. Set a constant GOP (group of pictures) so that keyframes arrive at predictable intervals. DASH/HLS segmenters rely on consistent I‑frame spacing to start segments; a wandering GOP breaks segmentation and forces downstream buffers to wait. A common rule of thumb is a 1‑second GOP: for 30 fps material set

-g 30 -keyint_min 30 -sc_threshold 0and disable B‑frames (-bf 0). This creates exactly one IDR frame every 30 frames, making it easy for transcoders to segment evenly. - Minimise muxing and packet buffers. Add flags such as

-flags low_delay,-fflags +nobuffer+flush_packets,-max_delay 0, and-muxdelay 0so that packets are flushed immediately rather than accumulated. These options are especially important for protocols like RTMP or SRT that otherwise buffer data internally. - Use SRT latency and mode parameters. When streaming over SRT you must specify an application‑layer buffer in the URI. It should be large enough to cover the round‑trip time plus any network jitter.

It generates a SMPTE colour‑bar video and sine‑wave audio, encodes them with x264 using the

zerolatency tune, enforces a 1‑second GOP, and sends the output as an MPEG‑TS stream via SRT. The latency parameter is given in microseconds (1.5 s), and mode=caller instructs the encoder to initiate the SRT connection:

iOS, Android playback

iOS and Android Playback Support for LL-HLS and LL-DASH.iOS

Low-Latency HLS is natively supported starting from iOS 14 and tvOS 14, including Safari and AVPlayer. Earlier versions fall back to standard HLS and cannot achieve true low latency. iOS Safari with LL-DASH? One more thing to note about LL-DASH is that it’s starting to be supported on MacOS/iPadOS and iOS too. MSE (Media Source Extensions) is supported by MacOS old versions, and iPadOS 13+. Finally thanks to Apple for starting to support MMS (Managed Media Source) in iOS version 17.1 (https://webkit.org/blog/14735/webkit-features-in-safari-17-1/). Guys at dash.js have supported this feature as well. Thus, for iOS you can use the following:- iOS 17.1+ with MMS support – LL-DASH with 2,0 sec low latency.

- iOS 14.0+ with LL-HLS support – LL-HLS with 3,0 sec low latency.

- iOS 10.0+ with HLS CMAF support – LL-HLS but with ±9 sec reduced latency.

- other iOS devices – traditional HLS MPEGTS with ±9 sec reduced latency.